O!

How is my dear little Earl Emory getting along?

-Carrie H. Blair, 1893

|

| Earl Emory Blair, 1893 |

What first drew me to Carrie H. Blair, my

great-grandmother’s sister, were lines she wrote about missing her baby

brother, Earl, while she was 90 miles away from home studying music at Grove

City College, Pennsylvania. “I’d like to have Earl here now and I’d kiss him

and shake him…,” she wrote in one of the three letters I have from her. It was

1893. One hundred years later, I was missing babies of my own — neighbor babies

I had grown to love but who had moved away, or babies I had cared for in day

care centers or as an au pair, and whom I’d had to leave.

When it comes right down to it, genealogy

is all about babies. With no disrespect to my childless-by-choice friends,

childless ancestors are usually disappointing. Dead ends. The hopes of finding

a second or third cousin down that particular branch (who might have old family

photos or letters or stories) are frustrated when you discover that that aunt

or uncle had no children.

Carrie’s letters were the first I knew

about her family, but as rich as they are, it took years of research to put

them into context, to learn more about each member of the family and the course

their lives would follow. And so it was that I worked backward from the

letters — from the intimate details of Carrie’s experiences as a daughter, sister,

sweetheart, and music student — to the colder facts that I discovered in Mount

Washington Cemetery, just outside of Perryopolis, Pennsylvania.

It was when I was in Mount Washington Cemetery

that I had the first of what would be many genealogical aha moments. At the

time, I didn’t know when Carrie had died, or whom she had married, or if she

had had children. But then I saw her headstone, near those of her mother,

father, and several siblings, and suddenly some of the puzzle pieces fit

together to create a new picture.

The last name on her headstone was

McIntire, surely the same McIntire (John Emory) whom she had mentioned fondly in

her letters. Near Carrie’s headstone was that of Wilbur Blair McIntire. There

were several photos of a little blond boy in my antique photo album that were

identified by that name, but I didn’t know who he was until that moment. Carrie

and Emory had had a son.

|

| Wilbur Blair McIntire |

Most startling was the date of her death.

She had died at age 29, the same age I was at the time.

|

| With Carrie’s headstone at Mount Washington Cemetery, 1993. Headstone reads: Carrie H. McINTIRE JAN 21. 1873 SEPT 1. 1902 |

A newspaper article about her marriage to

Emory in 1895 and the 1900 census gave me a few more peeks into her life. Her

marriage was recorded in The Weekly

Courier, Friday, November 1, 1895.

“W Luce,” who attended the groom, would later marry Carrie’s sister Sadie Blair. Watson and Sadie Blair Luce were my great-grandparents. I love the detail that they proceeded from one room in the house to another to continue the celebration.

Emory, Carrie, and their son Wilbur were living in Unity Township, Westmoreland County in 1900, and probably lived there as early as 1895. Though they were only about 30 miles from the farmland of Perryopolis, their surroundings were vastly different. The McIntires lived in Whitney, established about 1892 with the opening of the Whitney Mine & Coke Works, owned by the Hostettler-Connellsville Coke Company.

Emory, Carrie, and their son Wilbur were living in Unity Township, Westmoreland County in 1900, and probably lived there as early as 1895. Though they were only about 30 miles from the farmland of Perryopolis, their surroundings were vastly different. The McIntires lived in Whitney, established about 1892 with the opening of the Whitney Mine & Coke Works, owned by the Hostettler-Connellsville Coke Company.

Emory is listed as a bookkeeper in the

1900 census1 (he later became the payroll clerk for the H.C. Frick

Coke Company, which acquired the Whitney Mines in the early 1900s). He, Carrie,

and Wilbur most likely lived in the Whitney coal patch town, built especially

for mine workers and their families. Coal patch towns consisted of company-built

homes (with no indoor plumbing), boarding houses, a company store, and a school.

The undated photo below shows the rows of company houses and the company store,

the bigger building on the right. The smoke is coming from the Whitney Coke

Works.2

|

| Photo courtesy of the Virtual Museum of Coal Mining in Western Pennsylvania, http://patheoldminer.rootsweb.ancestry.com/whitney.html. |

The environment was hostile on many

fronts. The miners worked long hours in dangerous conditions for minimal wages, and the threat of strikes was often

met with violence. A similar adversarial dynamic existed between the U.S.-born and western

European workers and the more exotic eastern Europeans, whose language and

customs more noticeably marked them as outsiders.

Of more concern to Carrie was likely the

physical environment caused by the burning coal. A new wife and mother, she

would have faced daily unending battles against dust and soot, unable to keep

anything clean. The health hazards were even more caustic. Beehive ovens, used

to burn coal into coke, poisoned the surrounding landscape, destroying

vegetation and polluting the groundwater. The ovens released a “chemical

cocktail of ammonia, tar, phenols, and choking clouds of smoke…straight into

the air.”3

The toxicity of the smoke would have

irritated Carrie’s lungs, possibly exacerbating the tuberculosis that would

kill her in 1902. Tuberculosis was the leading cause of death in the U.S. at the

time, and the crowded living quarters of the patch town would have given rise

to tuberculosis outbreaks.3 Or perhaps Carrie caught the disease

from her mother, Josephine Gallatin, who died four months before her at the age

of 51, also of tuberculosis.

After Carrie died, Emory’s mother Jane King McIntire moved in with him to help raise Wilbur. Jane’s daughter Anna and son-in-law Charles McDonald also lived in Whitney, in the nicer company houses (with indoor plumbing) on Manager’s Row.

After Carrie died, Emory’s mother Jane King McIntire moved in with him to help raise Wilbur. Jane’s daughter Anna and son-in-law Charles McDonald also lived in Whitney, in the nicer company houses (with indoor plumbing) on Manager’s Row.

In the early 1920s, Wilbur married Emma

Watts and they had one son, Clifton, in 1925. Clifton never married and had no

children, so my hope of finding a direct descendant of Carrie’s ended.

However, my search did lead me to

discover a half-sister of Wilbur’s. Almost 18 years after Carrie’s death, Emory

married Maud Hugus, and their daughter, Jane King McIntire (named after her grandmother), was born in 1927,

30 years after Wilbur. Jane was born in Whitney but grew up in the nearby

Latrobe area, where she went to high school with Arnold Palmer and Fred Rogers.

She trained with the United States Nurse Corps and spent her early adulthood

in Pittsburgh. She moved to San Francisco in the mid-1960s, where she worked as

an organ transplant nurse at UCSF. And that was where I found her in the early

2000s, living only about 40 miles away from me.

I was thrilled to find this connection to

Emory and Wilbur, someone who could share stories not only about her father and

brother, but also about my great-grandmother Sadie, who stayed in close contact

with Emory and Wilbur after her sister’s death. Jane hadn’t heard any stories

about Carrie, but she did remember that Wilbur had a fondness and talent for

music, and she wondered if maybe he had inherited that gift from his mother.

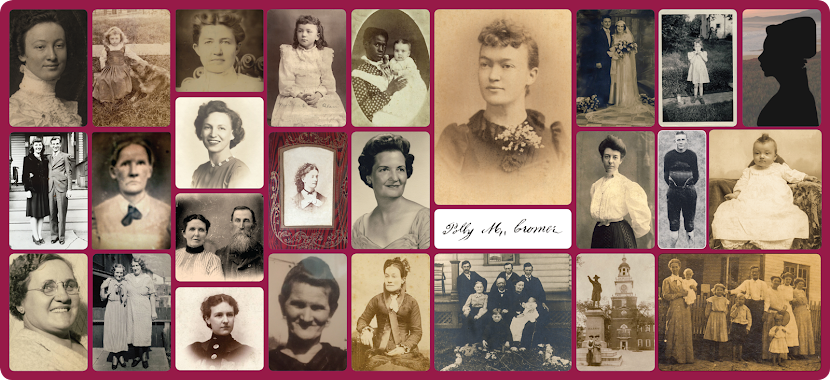

Until the other day, I thought I only had two other photos of Carrie. One of them is a tintype, with a young Carrie on the left, her brother Sam on the right, and an unknown girl — possibly a cousin named Leora Gallatin — in the middle.

* * *

Until the other day, I thought I only had two other photos of Carrie. One of them is a tintype, with a young Carrie on the left, her brother Sam on the right, and an unknown girl — possibly a cousin named Leora Gallatin — in the middle.

The other photo shows a group of young

adults and children in front of what I assume to be a schoolhouse. There are

two men in the doorway: Carrie is the second woman to the right of the men. Her

sister Sadie is directly to the left of the men. Their younger brother Sutton is

in the front row with his arm around a classmate.

I have scoured these faces looking for their

youngest sister Martha, but I think she must have already died, which would put

the date on this photo sometime after February 1893.

The other day, when I was digging out the photos of young Wilbur to scan for this blog, I took a closer look at a more candid photo of a family on a porch. I scanned that one and sent it to Jane, asking if she recognized those faces. She emailed back and said that it was definitely her dad. She assumed the boy must be Wilbur, and that it must be Carrie on the porch with them.

The other day, when I was digging out the photos of young Wilbur to scan for this blog, I took a closer look at a more candid photo of a family on a porch. I scanned that one and sent it to Jane, asking if she recognized those faces. She emailed back and said that it was definitely her dad. She assumed the boy must be Wilbur, and that it must be Carrie on the porch with them.

I studied the known photos I had of

Carrie, but couldn’t quite convince myself that the woman on the porch was she.

I cropped the photo closer and asked my daughter, to whom I have given these

exercises before. “That’s definitely Carrie,” she said decisively. “Look at her

face!” (Actually, I had been looking at her face…)

Gone are the fuller cheeks and the flower

of curls on her forehead, both seen in the studio photo I have of her when she

was in her late teens, and Carrie looks older and wiser than the 27 or 28 years

she would be here. But I had to agree that the brow and eyes were definitely

the same, and it’s been a real gift to me. I find it a comforting photo —

seeing her as a mother and wife, not too long before she died, but still

looking calm and content.

The uncropped photo of Carrie on the porch is actually a

perfect metaphor for this kind of research, with the blurry woman

unrecognizable in the front, but the other people gradually coming into focus

through a lot of research and a little bit of luck.

Sources:

1 The

1900 census reveals the diverse population of the area. The majority of the

families who lived in Unity Township were somehow attached to the coal and coke

industry, either as coal miners, day laborers, or coke drawer operators. About

half of the families were Pennsylvania or US born; the rest came from Great

Britain and Europe: Scotland, Ireland, Germany, Italy, and Austria/Hungary.

3 http://explorepahistory.com/hmarker.php?markerId=1-A-233

©

Kristin Luce, 2017