All this has happened before. And it will

all happen again. But this time it happened to Wendy, John, and Michael Darling.

-Walt Disney’s story of Peter Pan

My daughter was

born in 2003, just after genealogical resources began appearing online and

making family research much easier — easier, that is, for people without an

infant or toddler in their care.

My own research

was put on hold for several years, yet becoming a mother had made the research

that much more relevant. I had added a new generation to my family tree, and I

felt I could better connect to the generations of mothers before me. When I

read lines like the ones above in my daughter’s favorite books, they resonated

in a new way. When she started school and I had time to indulge in my dead

relatives again (my favorite kind, according to my brother), online resources like

Ancestry and Find A Grave had exploded (the U.S. census was fully digitized in

2006), and I could access documents and primary sources without having to leave

my home. But I was merely picking up on a journey that had started back in the

1970s.

In 1977, my

parents took my brother and me on a cross-country road trip. We flew from San

Francisco to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and picked up a new car, then followed a circuitous

route that took us to Washington D.C. and back across the country to our home

outside of Sacramento.

My father’s

mother, Mattie Lee Ames Luce McCanne, lived in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, in

a small town called Perryopolis, 30 miles south of Pittsburgh. Her home was one

of our stops.

|

| Fayette County, PA. Image courtesy of www.pafirefighters.com. |

My grandfather, Paul

Olin Luce, had died several years earlier, and it would be several more years

before Mattie Lee moved back to her home state of Arkansas. I was the only

granddaughter until 1986, and even though I was only 13 in 1977, Mattie Lee was

ready to trust me with some heirlooms. As we were leaving her house, she hurried

back into the garage and brought out a few boxes that she pushed into the car

next to me. It would be a decade or more before I explored the contents, but

when I did open the boxes, I found a small corner of the late nineteenth-century Pennsylvania countryside, filled with farmers and carpenters and their

wives and children, most of whom were related to me.

Of course, that

scene didn’t appear automatically. It took years of research to put the puzzle together, and this was in the 1980s and 1990s, long before anything was available

online. It required trips to the small San Francisco genealogy library that was

only open several days a week for limited hours (most of which did not

correspond with a college or work schedule) and visits to the Oakland

California LDS Temple, where rolls of microfilm were stored in the basement and which was the only local option for finding census information at the time. It

also required a trip back to Perryopolis, to wander through the cemeteries looking for names and connections, and hours in the Uniontown Court

House, where I found wills and other documents.

But the most

precious papers I have couldn’t be found in the usual places. The only

reason I have them is because my great-grandmother Sara “Sadie” Blair Luce Bryson

saved them, and then Mattie Lee, Sadie’s daughter-in-law saved them. These are

letters to and from Sadie, her brother Sam, and her sister Carrie, written

in the springs of 1892 and 1893, when first Sam, and then Carrie, were away

from home at school.

|

| Letter from Sadie to Sam, April 1892 |

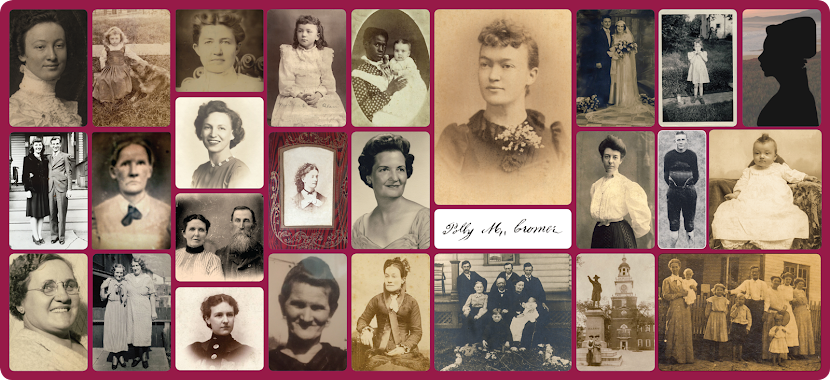

Sadie and Mattie

Lee also saved an old photo album filled with pictures of the family, many of which

(not all) were identified, so I was able to put faces to the names, and fill

the Fayette County countryside with fully imagined people to people my own little genealogical

dollhouse.

Here is that

family: parents Olin Sutton (“O.S.”) and Josephine and children Carrie, Sam, Sadie, Sutton,

Martha, and Earl.

In 1892, the year

the first letters were written, Fayette County was in the midst of a population

explosion fueled by the coal and coke industry. Immigrants from eastern and southern Europe and former enslaved people from the South changed the makeup of

what had been a bucolic farming community settled by German and Scottish

immigrants in the early nineteenth century. My Blair family was straddling

this shift. The father of the family, O.S. Blair, had

transitioned from building barns to building mine shafts, and ten years later,

in 1902, he would become the assistant superintendent of the Washington Coal &

Coke Company, leaving his family’s rural roots behind.

The letters I have

were written right before these changes took place. Although O.S. Blair had not

yet attained the professional and economic success that he’d see in the next

decade, he was still able to send two of his children to college. Samuel Gallatin

Blair, the oldest son, was at a “normal school” — what would become known as a

teacher’s college. A year later, the oldest child, Carrie, went to study music

at Grove City College, 90 miles from home. Sam’s letters are playful and

engaging, revealing a loving and fun relationship with his younger siblings

Sadie, Sutton, and Martha. Carrie’s are more serious, focusing on her experiences as a new college student, but like Sam’s, her words illustrate

a deep attachment to her family and home.

These words, more

than the primary sources or histories or even photos, offer a peek into their

lives, a window through which I can look back into 1892 Pennsylvania and see my

little doll family going through their daily lives — at work, at play, and at

school — before and after personal tragedies that would reshape their lives,

constantly forcing the family to regroup and move on, just as each new generation

does.

Sources:

© Kristin Luce, 2017